In Cambodia, the realms of art, craft, and spirituality are deeply intertwined. Step inside any Cambodian pagoda (Wat), and you are immediately immersed in a world where handmade objects are not mere decorations, but vital components of religious expression, ritual practice, and the creation of sacred space. From intricately carved statues to delicate floral offerings, traditional handicrafts are tangible manifestations of devotion (sraddha), skill (kusala), and the enduring connection between the Cambodian people and Theravada Buddhism.

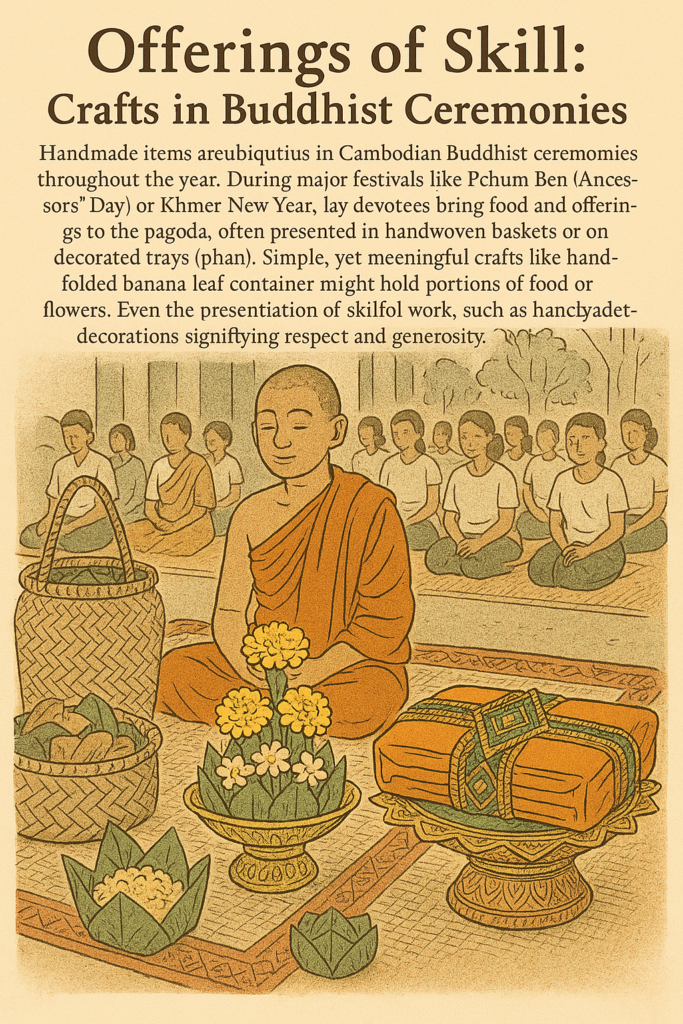

Offerings of Skill: Crafts in Buddhist Ceremonies

Handmade items are ubiquitous in Cambodian Buddhist ceremonies throughout the year. During major festivals like Pchum Ben (Ancestors’ Day) or Khmer New Year, lay devotees bring food and offerings to the pagoda, often presented in handwoven baskets or on decorated trays (phan). Simple, yet meaningful crafts like hand-folded banana leaf containers might hold portions of food or flowers. Woven mats provide seating for monks and laypeople during sermons and rituals. Even the presentation of offerings, such as monk’s robes during the Kathen ceremony, often involves elaborate, handcrafted decorations signifying respect and generosity. These everyday crafts, elevated by their ceremonial context, underscore the integration of skillful work into religious observance.

Adorning the Sacred: Altar Decorations

The main altar (preah put), where the principal Buddha images reside, is the focal point of any pagoda’s prayer hall (vihear). Monks and skilled lay artisans lavish care on decorating this sacred space, employing various crafts:

- Carved Elements: The altar structure itself may feature intricate wood carvings. Elaborate carved wooden stands hold scriptures or support offering bowls.

- Ceremonial Umbrellas (

Chat): Multi-tiered ceremonial umbrellas, often adorned with gilded carvings or fabric trim, flank the main Buddha images, symbolizing royalty and protection. - Banners and Hangings (

Tung): Colorful banners, sometimes painted or featuring appliqué work with Buddhist symbols, hang from ceilings or pillars, adding to the temple’s vibrancy during festivals. - Floral Arrangements: While fresh flowers are common, handcrafted arrangements (discussed below) also play a role in ensuring the altar is always beautifully adorned.

The creation and maintenance of these decorations are acts of devotion, contributing to an atmosphere conducive to reverence and meditation.

Ephemeral Beauty: Paper and Wax Offerings

Given the tropical climate and the desire for constant adornment, Cambodians have developed traditions of crafting long-lasting floral offerings:

- Paper Flowers: Intricate flowers are meticulously folded, cut, and assembled from colored or gilded paper. These are used as altar offerings, decorative elements on ceremonial structures (like funeral pyres or parade floats), or presented as devotional gifts, offering lasting beauty where fresh flowers might quickly wilt.

- Wax Creations: Skilled artisans, sometimes monks themselves, craft stunningly elaborate sculptures from beeswax. These often take the form of intricate floral arrangements, miniature stupas, mythical creatures, or other symbolic shapes. Wax offerings are particularly prominent during major ceremonies and represent considerable skill and devotion. Their eventual melting or replacement also subtly reflects the Buddhist teaching of impermanence (

anicca).

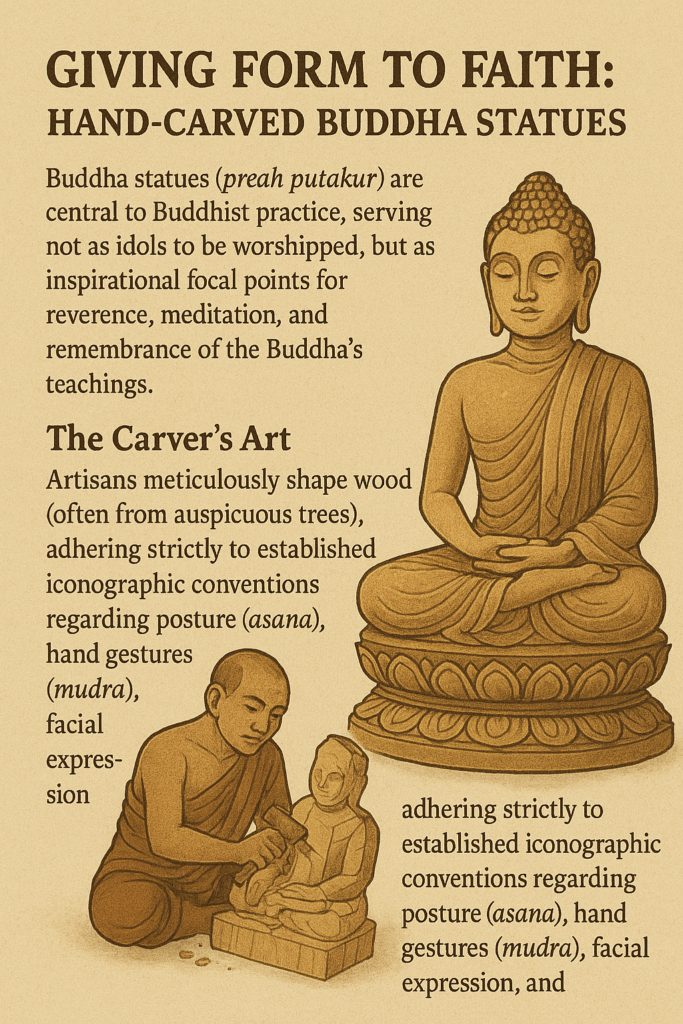

Giving Form to Faith: Hand-Carved Buddha Statues

Buddha statues (preah putakor) are central to Buddhist practice, serving not as idols to be worshipped, but as inspirational focal points for reverence, meditation, and remembrance of the Buddha’s teachings. The creation of these statues, especially through hand-carving in wood (a common material alongside stone and bronze casting), is considered a deeply meritorious act:

- The Carver’s Art: Artisans meticulously shape wood (often from auspicious trees like jackfruit wood) using traditional tools, adhering strictly to established iconographic conventions regarding posture (

asana), hand gestures (mudra), facial expression, and proportions. This requires not only technical skill but also a meditative focus and understanding of Buddhist principles. - Spiritual Significance: The completed statue becomes a sacred object, embodying the qualities of the enlightened one. It serves as a visual aid for teaching, a recipient of offerings and prayers, and a source of peace and inspiration for the community. The care invested in its creation reflects the reverence accorded to the Buddha.

Counting Blessings: Traditional Prayer Beads (Ksae Kor)

Prayer beads, known locally as ksae kor or sometimes chkranok dey (if made from clay pellets), are used by monks and devout lay Buddhists primarily as a tactile aid for counting prayers, chants (mantras), or breaths during meditation.

- Materials and Making: They are traditionally crafted from various materials, including wood, seeds (especially seeds from the Bodhi tree or related species), stone, bone, or historically, clay. The beads are shaped, drilled, smoothed, and strung together, often finishing with a tassel or larger ‘guru’ bead. While simple plastic beads are common today, handcrafted ones hold special significance.

- Symbolism: Often consisting of 108 beads, this number holds various symbolic meanings in Buddhism, frequently related to the 108 human desires or defilements to be overcome on the path to enlightenment. Using the beads helps maintain focus and mindfulness during devotional practices.

Rebuilding the Faith: Handicrafts and Temple Restoration

Handicrafts are inextricably linked to the physical construction and restoration of Cambodia’s thousands of pagodas. Building or contributing to the restoration of a temple is considered highly meritorious (tham thveu bon), and this often involves the skills of numerous craftspeople:

- Carving: As detailed in article 10.2, wood and stone carvers create essential decorative and structural elements – pillars, ornate door panels, window shutters, intricate roof gables (

Wat kor), and decorative friezes – often needing to meticulously replicate historical styles during restoration. - Painting: Skilled artists create vibrant murals (

kbach chit) depicting Jataka tales, scenes from the Buddha’s life, or local folklore, adorning the interior walls of thevihear. Restoring these paintings requires specialized knowledge. - Metalwork: Artisans craft decorative metal elements like the graceful flame-like finials (

chofa) adorning pagoda roofs. - Other Crafts: Depending on the temple, other skills like decorative tile work or specialized masonry might be involved.

These contributions are not just labor; they are offerings of skill infused with religious devotion, ensuring the continuity of sacred spaces for the community.

A Sacred Tapestry

In Cambodia, handicrafts are far more than economic activities or aesthetic pursuits; they are fundamental threads in the rich tapestry of religious life. They provide the essential objects for rituals, create spaces conducive to worship, give tangible form to profound beliefs, and aid in devotional practices. The skill, care, and faith invested in crafting these items infuse them with spiritual significance, making them powerful expressions of Cambodian culture and Buddhist devotion. This deep connection between craft and faith is vividly present in pagodas throughout the country, including the beautiful Wats found in and around Battambang, offering a constant, tangible reminder of the sacred interwoven with the everyday.